Reproduced by permission of the artist.

To understand if Ithaca's success is a fluke or if the concept works in other locations, I sought to interview persons who had begun or were running programs modelled after Ithaca. Glover has produced a how-to book on Ithaca's story, and distributed it to interested parties globally. But would that how-to book lead others through a twelve-step program for success, or would it raise their hopes before they discovered by much effort that a local currency was not feasible in their community? Through a series of flowing conversations and a standard survey, I hoped to learn some of the details about their programs, both quantifiable data and qualitative observations.

I attempted to contact every single Ithaca HOURs-style local currency program

in the United States. Unfortunately, no organisation is actively maintaining

a phone book or address list for these groups. I compiled a list by combining

three online local currency directories,1 and added other currencies

as I found references to them across web pages, through personal referrals,

and Internet-based discussion groups. Each directory had its share of errors

with contact information and program status as much as three years out of date.2

Acknowledging that they does not possess the resources to continually seek updating

information, they say they rely instead upon currency programs to provide updates

of their own information. Even these updates are not always entered. Donald

Hof of the Cascadia Hours Exchange has tried numerous e-mails and phone calls

to have his first name changed from Don to Donald in each directory; none has

made that change.3

A question of bias could be raised in that only those programs which were known to the sources searched have been contacted; others might be flourishing in isolation and be missed by this survey. This possibility is unavoidable, uncorrectable, unlikely, and irrelevant since this project was not intended to statistically define the depth and breadth of the local currency movement in terms of number of members, quantity of trades, or effect on the economy. No master list of the population of HOURs programs exists against which to compare the traits of the programs which were successfully contacted and extrapolate the total value or power of the movement. Rather, an understanding of the effectiveness of these programs and common factors that serve to help or hinder the creation of a local currency were the goals of this study. The inclusion of numerous defunct currency systems in the listing, and my decision to learn of their struggles in addition to the successes of other programs, serve to eliminate the bias that would come from solely examining successful programs. The lists from which the data was compiled included not only then-active programs but persons who had been considering starting programs, so that those who were considering starting currency programs but decided against it could have their thoughts and reasons considered as well.

Table 1. Currency Co-ordinator Survey Response Levels.

| Percentage of Listings | Percentage of Contacted | Percentage of Sent | ||

| Listings | 105 | 100 | ||

| Failed to contact | 60 | 57 | ||

| Contacted | 45 | 43 | 100 | |

| Defunct or dormant | 12 | 11 | 27* | |

| In operation | 21 | 20 | 47* | |

| In planning | 3 | 3 | 7* | |

| Never started | 9 | 9 | 20* | |

| Surveys sent | 40 | 38 | 89 | 100 |

| Surveys received | 22 | 21 | 49 | 55 |

| Surveys not received | 18 | 17 | 40 | 45 |

* Totals do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Out of 105 listings for potential local currency programs across the United States, I managed to successfully contact 45. The remaining 60 either did not have current and working phone numbers or did not return calls. Though I was able to contact 45 persons to determine the status of their representative programs, in five of these cases I was unable to send a survey to learn more details because the individual whom I contacted knew the status of the project but was not the primary person responsible for the program, and could not get me in touch with them. Four of these never started and one had ended. Table 1 summarises the status of the phone calls made and the surveys sent out.

Motivation for Local Currencies

Reasons for starting local currencies varied from person to person according

to their interest. Sometimes the motivations for those starting the currency

differed from the reasons for potential members to join that were listed in

their publicity. To see all the different viewpoints presented, one would think

that local currency was a cure-all. Though the benefits listed to potential

members are generally cut from the same cloth as the nine benefits Ithaca HOURs

lists, they differ from why co-ordinators started.

Gary Pace saw it as a launching point for other activist movements. "It seemed like a good concrete organising tool around local empowerment and creating alternative structures and disengaging from the corporate system that exists right now."4 A community organiser and sustainability activist by nature, Pace helped start Mendocino's SEED program before moving to an intentional community. A friend of Pace who had already disengaged from the corporate system in some ways, Dale Glaser's home is entirely powered by renewable energy. He saw local currency as a way of confronting cynicism.

Here's an example of where it's easy to say, "Oh, this won't work," or "This is going to be too hard" . . . And that's true for anything. The question is, "Are we big enough to do something that might require a little bit of effort but has this vast reward?"5

Glaser worked on Ukiah HOURs with King Collins, who saw cynicism as only one

element of a large system that needed to be confronted. "The only reason

someone would design a local currency is to transform the social fabric,"6

he commented after dinner when I asked about his involvement. A reader of Wendell

Barry, his economic viewpoint tended toward Marxist, quite different in many

respects from a third member of the Ukiah HOURs team, Ken McCormick. The owner

of a print shop, his Republican and Libertarian leanings caused him to be "concerned

about the collapse of the world economy, and he wanted to be involved in HOURs

because he saw the working of the economy collapsing," according to the

fourth member of the core group, Larry Sheehy, who himself joined because he

was convinced that "local currency had the potential of contributing to

the positive transformation of the economy . . . moving it back to the local/bioregional

from the present disfunctional globalized version."7 Two

other organisers of Ukiah HOURs joined to increase community and out of frustration

with the federal monetary system.

With this much variety of motivation in one locale, it should not surprise

the reader to learn that similar variety showed up in conversations and survey

responses from communities nationwide. From economic interests such as increasing

earning power, promoting a living wage and equality of income, and guarding

against potential global financial meltdown or globalisation to social concerns

like education about money's functions and rebuilding neighbourhoods and environmental

values including local production, sustainability, and creating an ecologically-sound

money, motivations for starting local currency programs ranged across the board.

Nonetheless, these three strong themes of economics, society and environment

continually resonated throughout the community of co-ordinators.

The largest lesson to draw from the variety of different viewpoints is that

the success of local currency is being measured on other levels besides the

economic for most of these persons. Barbara Conn of Buffalo Mountain HOURs noted

that their currency was circulating quite slowly, but she still considered it

a success. She related the thoughts of the currency's founder David Briar, who

passed away a few years ago.

He said it didn't concern him if people weren't using it right now. He felt that it was important to have the system in place and that when people need to use them, they will. And when they're backed into a corner, they'll have this to turn to.8

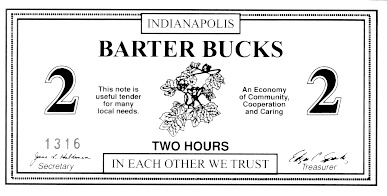

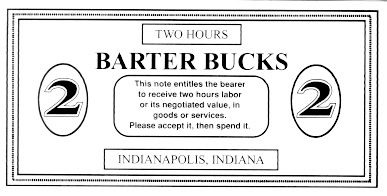

Many persons have joined or promoted local currency as a hedge against potential future uncertainties as yet unseen. Unfortunately, if co-ordinators have few concerns with the current economic viability of these programs, looking solely to the future to vindicate them, their programs may never survive to meet the future. As John Gibson said about the defunct Barter Bucks program in Indianapolis, Indiana, "I'm not saying it was a failure but it was an experiment that didn't last as long as we'd like it to."9

Figure 14. Face, reverse of Two Barter Bucks note from Indianapolis, Indiana, 1994.

Challenges to Local Currencies

Conversations with each person served very informative and revealed several

key patterns and elements that affect the viability of local currencies. As

I examined the challenges that local currencies faced, I became aware that to

call the spread of the Ithaca HOURs program a movement would be deceptive. A

movement implies structure and organisation, conjuring up images of strategists

and directors overseeing local chapters in a hierarchical structure. Though

many voices in unison proclaim Ithaca as their standard and Paul Glover as their

standard-bearer, quieter voices speak of problems with the Ithaca HOURs model,

either explaining how Ithaca possessed certain advantages in running such a

program without which their respective communities are denied the chance at

grand success, or advocating changes in the design of the currency program to

suit one or more policy visions of theirs.

First and foremost on the lips of many was the need for a full-time co-ordinator.

The reputational capital that must be built to help serve as backing for a fiat

currency cannot be formed part-time. Steve Gorelick of Green Mountain Hours

said, "We're always in need of more volunteer help to get it to the next

level. We don't have a Paul Glover among us who's devoted to promoting it full

time."10 Glover's total commitment to the success of

HOURs greatly decreased information costs both external and internal to the

co-ordination of the program. Externally, businesses and individuals that have

questions, whether about applying for membership, issuance details, finding

trading partners, purchasing advertising, or any other items, have only to keep

track of one person to knowledgeably manage and handle their issues. Being the

figurehead for some time also gave Glover the advantage that he could achieve

greater prominence and visibility throughout the community as the HOURs co-ordinator.

Sita Francia told me about one challenge of Mendocino's local currency program:

"There's a couple people who are the contacts, and a lot of businesses

that I've approached have never been approached because there's no paid staff

and there's no particular person who's dedicating themself to be that contact

for businesses."11 One individual putting forty hours

per week into a project can accomplish much more than four individuals each

working ten hours per week because his dedication can greatly reduce the information

costs of monitoring the program's success. Not only can he oversee the act of

systematically inviting new businesses and individuals to join, but also working

to understand the needs of the network of members that form the HOURs economy.

Popular businesses often end up being major earners of HOURs, and assisting

those businesses to find outlets for their accumulated HOURs is a challenge

requiring an extensive knowledge of the goods and services being provided by

other HOURs members. A full-time co-ordinator is part networker, part marketer,

and part information desk, part community builder, and part as he

attempts to pair the needs of members with too many HOURs with the services

of those desiring more HOURs. One reporter commented, "It takes a confident,

well-versed person to convince people that [using local currency] could benefit

them, their friends and their town."12 Even when everyone

else is interested in making it work, it takes a strong central leadership to

co-ordinate and orchestrate it during the initial stages. Devin Scherubel provided

an example of the value of leadership.

About three months after starting [Columbia HOURs], I got hired full time as an activist, sucked up into the forest protection movement. Nobody else had the time to put into it. Other than that, it was really good. Local businesses were interested, the community was really responding, and the press was highly positive.13

Columbia HOURs suffered because of a lack of people power at the helm. Had

Scherubel been hired full time to run Columbia HOURs, chances are it would not

have become inactive. Finding a talented leader is a difficult task. Perhaps

Kathy Witkowsky

summed it all up when she explained why Missoula HOURs never began. "We

needed the right combination of someone who was fiscally conservative and had

credibility in the community. You have to be known as someone who's not a flake,

with longstanding reputation in the community."14 Lacking

Glover's track record for activism and commitment may have been one of the reasons

many co-ordinators did not succeed in promoting their new ideas. Becaues of

his prior efforts in Ithaca, community members and leaders could trust that,

regardless of whether Glover's ideas ultimately worked or not, he would be committed

to his cause.

Trust is a difficult thing to establish, being built up slowly over time. Stability

in both leadership and community were therefore cited as elements that could

make or break communities. In Olympia, Washington, Gail Sullivan has seen community

instability threaten the local currency's viability. "Many members are

college students who don't let us know they've left after graduation. Because

of the continuous turnover, it's been difficult to maintain the integrity that

people need to feel their currency is backed by."15 Santa

Fe HOURs has seen a similar difficulty with a massive transient population.

If these currencies are backed by the "talents and labor of you and your

neighbor," as one local currency phrases it, as the number of known and

trusted acceptors of a currency declines, so will the currency's value. Stability

in the program's leadership is factor of similar importance. Noted one of the

co-ordinators of REAL Dollars in Lawrence, Kansas, "I think these systems

work as long as there's someone willing to devote himself to the system over

the long term."16 With active leadership, current and

potential members can place greater trust in being able to find outlets for

their earnings, without which trust they are unlikely to accept the currency.

Unfortunately, as Jennifer Kreger told me, "The average time to burnout

is eighteen months."17 She was only one of numerous co-ordinators

who highly recommended applying for a grant to fund a part-time or full-time

position since volunteer labour has proven unreliable and insufficient for running

all the administrative and visionary elements of a local currency.

Many programs are challenged by efforts to involve enough businesses providing non-luxury goods to keep the program in operation in the long run. Timothy Mitchell noted, "Because of the nature of the things you offer, you get this whole community of starving artists trying to support starving artists. If you really want to support the starving artists you need to get the middle class involved."18 Man cannot live by paintings alone, but must pay for produce and other foodstuffs, clothing, entertainment, and home maintenance as well, just to name a few categories. University of California at Santa Barbara student Tony Samara lamented, slightly exaggeratedly, that "We didn't pay enough attention to what skills our list lacked. For every carpenter, plumber, etc. we had 50 masseuses, tarot card readers, and holistic healers."19 This makes it quite difficult to meaningfully incorporate local currency into one's daily life. The decision of community anchors such as the local food co-operative, the pharmacy, and the coffee shops to accept or not accept local currency has much power to affect the scope and longevity of local currency projects.

Surveying Co-ordinators

In addition to telephone interviews, I composed a standard survey which I sent

to gather information on a number of issues that I thought should be addressed

by all co-ordinators on the basic design elements of their HOURs program, some

common places for variation within the program, and the specific difficulties

they encountered with the program.20 The Ithaca HOURs website

has stories of success galore, and often when discussing a pet project, one

can become quite protective of it, desiring to represent it in the best possible

light as an act of self-affirmation. These questions were intended to guide

respondents into a full reflection on the project in order that a proper overall

picture could be presented, and some chose to add comments outside the questions

presented when returning their surveys.

Though the most proper survey methodology would require that all the surveys

be sent at one time and in the same format, I did not do this for a number of

reasons, but instead sent them out over a period of weeks and sent some via

postal mail and others as electronic mail. The outdatedness of the list from

which contact was attempted would have made any usage of the response rate as

a measure of the representative nature of the data null and void. A survey with

a low response rate would potentially be criticised on the grounds that a non-representative

sample replied, introducing questions of selection bias which could not be answered

definitively absent further data about the individuals which responded and those

which did not.

I insisted upon establishing telephone contact with an individual prior to

sending out a survey to avoid having my response rate unnecessarily diluted

by mailing to expired addresses. Further, with such a small survey population,

a higher response rate becomes more necessary if one is to ensure the sample's

representative nature. Telephone contact prior to the arrival of the survey

helped recipients understand the value of the survey and let them know that

their contribution was important. It further provided opportunities for conversations

up to an hour in length, which served to flesh out the variations and common

themes present in the programs surveyed. In one sense, these conversations were

more valuable, if less standardised, than the actual surveys mailed out.

The primary reason to send out all surveys simultaneously would be to avoid a bias in some of the responses due to timing. A researcher studying views of the American Internal Revenue Service would not want to have sent out half her surveys in February and the remaining half in mid-April just after tax returns have been filed. The major events which would have transpired in between her two mailings would have likely changed respondents' opinions radically. By a simultaneous mailing, "the potential influence of events outside or unrelated to the study ... can be assumed to be equal for all recipients of the questionnaire."21 In this survey of program co-ordinators, there are few events that would tend to skew responses across time, barring a massive global economic downturn that destabilised the dollar. As the Y2K bug had come and gone relatively without incident, it was decided that simultaneity was not a critical factor in the mailing. Whether the survey was a timely follow-up to telephone conversations seemed the much more pressing concern, so surveys were sent out electronically or by postal mail within three days of establishing telephone contact. This took place over a three-month period of time, from late September 2000 to early December 2000.

Table 2. Summary Statistics of HOURs-style Programs Surveyed.

| Mean | Median | Mode | Range | |

| Value per unit † | 10.7 | 10 | 10 (n=16) | [10, 20] |

| Months Circulating † | 30.6 | 31 | 24 (n=3) | [0, 60] |

| Months Planning † | 13.3 | 12 | 12 (n=6) | [3, 36] |

| Units in Circulation ƒ | 920 | 540 | 0 (n=5) | [0, 4000] |

| Units per New Member ƒ | 3.4 | 3.75 | 4 (n=7) | [1, 5] |

| Units per Renewal § | 0.75 | 0 | 0 (n=10) | [0, 2] |

| Member Base ‡ | 178.6 | 120 | 0 | [0, 1030] |

| Individuals ƒ | 161.5 | 100 | 0 | [0, 800] |

| Businesses ƒ | 35.5 | 15 | 10 | [0, 230] |

| Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Fixed Exchange with US$ ‡ | 11 | 58% | 8 | 42% |

| Exchangeable for US$ ‡ | 2 | 11% | 17 | 89% |

| Networking with Other Programs ‡ | 7 | 37% | 12 | 63% |

| † n = 20 | ‡ n = 19 | ƒ n = 18 | § n=16 |

Out of twenty-nine surveys sent by postal mail, fifteen responses were received,

and seven of eleven surveys sent electronically were returned. Two mail respondents

had not actually involved themselves with HOURs-based exchange programs, but

responded nonetheless with their observations about alternative exchange systems

and their involvement in some of them apart from the HOURs model. Having incorporated

discussion of some of the qualitative responses on the survey into the previous

section, this current section will focus on some of the quantitative elements

of the surveys, elements which were not asked during telephone conversations.

In four questions, I specifically excluded Philadelphia's Equal Dollars from

the statistics reported.22 Equal Dollars have a face value

of one dollar each, and $81,000 of them have been distributed into the community,

50 Equal Dollars to an individual joining and 150 Equal Dollars to those businesses

joining. Inclusion of Equal Dollars in these statistics would have created a

massive outlier which would serve to dramatically alter some of the reported

mean values, having twenty times as many units of currency in circulation as

the next highest respondent. The face value of Equal Dollars does not greatly

alter any other questions, so Philadelphia's data has been included in those

instances. It does raise the membership data means but not so substantially

as to be dangerous.

One section of the survey not listed in Table 2 is the membership fee structure.

This has been perhaps the area of greatest consistent disagreement between programs,

in part because two competing elements have been seen to govern the fee structure.

The first is the desire of many of these programs not to be seen as in competition

with federal currency. They do not wish to sell their currency at face value

out of a belief that this would be perceived as making their currency just a

substitute for federal currency in traditional economies, rather than being

a portal to a new type of trading community.

Larry Sheehy commented, "The purpose is to get the program going and to

entice people to take part in it. Most all of the programs have some twenty

to forty dollars as a 'priming the pot'."23 Getting people

excited about local currency was one reason money was handed out freely. Sarah

Sieverson was one of few co-ordinators to express concern about the process,

saying, "I felt it should be dollar-for-dollar in the beginning. It seems

to devalue the currency to start without full backing one-to-one."24

The second element affecting membership fees is the need to pay expenses of

publication, advertising, and other administrative costs. As Susan Hofberg of

Mendocino SEED shared, "It's very expensive to print up the currency and

the newsletter. . . . Just to do that is really all that we've got money to

do, because the money comes from people's memberships and once you have that,

that's it!"25 Expenses such as these cannot be met by

local currency alone; the widely-circulated story that Glover convinced David

St. George of Fine Line Printing to accept HOURs as payment for printing up

his new local currency is incomplete, as he only took 10% in HOURs.26

Thus, initial membership fees ranged from free to $10 per person, with three-quarters

of programs charging at least $5 to join. Renewals were tricky as well; some

co-ordinators considered that membership was for life, while others felt that

renewal fees were appropriate. Renewal fees were accordingly split in three

almost-equal groups between those making renewal free, those charging $5, and

those charging $10.

Ithaca Money gives out HOURs upon renewal as a way of ensuring its membership

directory is kept up-to-date. This helps keep the perceived value of the currency

higher because users do not have to thumb through a seriously-outdated directory.

Since this renewal is an agreement to back the currency with one's own services,

Ithaca Money is receiving a service from its members, and seeks to compensate

them accordingly. Seven programs do likewise and ten do not add more money into

circulation at that time; three did not respond to that question.

It was surprising to note that 42% of co-ordinators did not consider their

currencies to have fixed exchange rates with federal currency. For legal and

taxation purposes, and for explaining them to potential members, every currency

I have come across has equated their unit of measurement to some quantity of

federal dollars. This cannot be explained by declaring that they misunderstood

the question, since the question immediately prior asked if they would redeem

their currency for federal currency upon request. One possibility I refer to

as the "floating anchor" scenario. Though currently pegged as equivalent

to a certain dollar value, in the event of the dollar's massive devaluation,

they plan to repeg their local currency's value at a different level, perhaps

moving from $10 to $12 or even $20 per HOUR, so as to prevent devaluing their

currency in terms of the goods and services produced and purchased locally.

It is a fascinating vision, though one which seems like it might have difficulties

in implementation. Determining the new level, communicating this change in valuation,

and assuring the members that their currency was not going to subject to massive

fluctuations and uncertainty would take a lot of work. If co-ordinators are

prepared to or even planning on doing this at some time in the future, it may

explain why they did not declare their currencies as possessing fixed exchange

rates.

Several of the programs I came in touch with had significant deviations from the Ithaca model, and two of these were explicitly different enough that their ideas merited discussion apart from the general discussion of other programs.

SonomaTime

Having dealt previously with the likelihood of Ithaca's program raising the

minimum wage by attempting to psycholinguistically equate an hour of time with

an HOUR of currency, I was intrigued when I encountered SonomaTime's program,

which requires hour for HOUR exchanges, to "neutralize the fear, anger,

and isolation often found in association with competition for dollars and the

drive for profits"27 as well as to ensure higher and

more equal income for all involved. From the perspective of current taxation

structures, it seems ridiculous to desire to raise every individual's wages

within a community. Suppose every member were previously earning $10 per hour

and now agrees to exchange one HOUR for an hour's labour. In the SonomaTime

program where this forced exchange level is being promoted by the program's

leaders as a way of respecting every individual equally, this idea's implementation

will have dangerous consequences. Due to the cost of living in California's

wine country, a Sonoma HOUR is pegged at US$20, which effectively doubles everyone's

income. This forces each member of the community to contribute to the Internal

Revenue Service and the California Franchise Tax Board more than twice what

they previously had to pay because of the nature of progressive taxation and

standardised deductions, which have been responsible for other perversions such

as the marriage tax penalty debate. Not only will individuals owe in excess

of twice their previous tax liabilities, but the state and federal governments

have yet to accept Sonoma HOURs in discharge of these debts. The result of a

successful program to radically boost the minimum wage through a local currency

would be the speedy draining of federal currency from the community, forcing

it either to become vastly more self-sufficient or to accept lower wages. Raising

the minimum wage does therefore not enhance the community's well-being. Ironically,

if every individual agreed to value their HOURs at rates such that their hourly

earnings were below the wage rates in other communities, their tax burdens as

a percentage of their nominal income would lessen greatly. Only through that

act of humility and overcoming of greed however will they escape their perceived

shackles.

The penalty of progressive taxation structures to penalise increased wages

aside, one cannot forcibly equate an hour of one man's time with an hour of

another's when the two are not providing the same service. Numerous communities

have maintained babysitting co-ops for years where mothers pay other mothers

for babysitting services solely in hours of time redeemable for babysitting

services, but the service rendered from providing an hour of peace and quiet

to run errands or just relax without children underfoot may be presumed approximately

equal across all mothers of children of babysitting age. Even these co-ops do

not propose to value an hour of childcare equally for all mothers, assessing

a higher fee in hours for multiple children than a single one.

In a broader economy, some may freely choose to trade at a fixed exchange rate

of one hour of time for one HOUR of local currency, but it is a very special

type of individual who does this. Either each individual believes himself to

be obtaining the superior deal, getting more or certainly no less from another

than he gives, or he is not concerned with obtaining the full market value of

his currency. The former will not believe he must put forth his best effort

lest he trade with someone else who did not put forth her best effort and lose

from the exchange, and should be considered a shirker or a thief, while the

latter will be interested not in a price economy but a gift economy, assigning

value to something merely because it was done by someone else for him and not

solely in proportion to the usefulness of the service, much like a grandfather

paying his eight-year-old grandson to weed the vegetable patch. Whether this

person has any value ultimately for a currency rather than relying solely on

barter or communal giving remains to be seen. Thus the two types of persons

who would most readily assent to this system of exchange are not interested

in properly ensuring that the currency is traded for something of value. The

thief wishes not to give full value, and the grandfather asks not for full value.

Without assurances that value is being maintained and transfered, the system

will break down.

Is it possible that instead members possess a community value function, declaring

that it is okay if they receive less because there will be a transfer of value

to the community, much as philanthropists and funders of public works projects

derive value from knowing that others benefit from their munificence? One person

and one person only benefits from this in the long run, and that is the man

who provides services and receives a higher price than he expected.28

The purchaser of services who agrees to hour for HOUR exchange will see price

inflation until the standard rate for services is the level he has continually

generously paid, negating the generosity of his giving unless he is willing

to require even less for his payment. As a mere transfer of wealth and not a

creation of any, it benefits the community none, and to the extent that price

inflation affects others, it will be a negative impact.

Inflation, as Friedrich Hayek notes, is not a simultaneous effect across the board; people do not go to sleep one day and wake up the next morning with prices two percent higher. Rather, one individual figures out that there is more money in the system and starts paying and charging higher prices, and others follow suit as this information trickles through the system. It is not the change in the general price level which is the most disruptive, but the change in relative prices between goods that distorts the system of prices into poor and mis-allocated production. Hayek further notes that inflation cannot come from an individual charging higher prices unless someone else produces more money to permit everyone to purchase everything they previously were consuming. Otherwise, they will merely reallocate their money and cut back on other expenses to meet the increased cost in this one area, with the one downside being potentially increased unemployment in these other areas.29 Since local currencies are often created with one of their goals being to increase employment, it is likely that SonomaTime would willingly fund this inflation under the hopes that putting more money into circulation would increase employment. These inflationary predictions and extrapolations of course are predicated upon the successful takeover of a significant portion of the market by SonomaTime, though it seems ironic to rejoice that SonomaTime will not cause massive inflation if the reason for that is from lack of market presence.

REAL Dollars

One local currency program with great promise is Lawrence, Kansas's REAL Dollars.

Begun in mid-2000, they have not been around long enough to know by community

usage patterns its likelihood of success, but its design is very appealing.

Dennis "Boog" Highberger, one of the organisers, informed me, "We're

actually selling the REAL Dollars dollar for dollar, putting U.S. dollars in

a credit union, using interest to fund the program."30

Within months of their kick-off, they had $5,000 worth of REAL Dollars in circulation,

demonstrating at least the initial interest of the community; . Full redemption

and conversion without charge is promised by its co-ordinators. This should

increase confidence in the money in that individuals should be quite likely

to accept it and believe that it will hold its value; the down side from the

organisers' perspective may be that there is no incentive built into the system

to encourage REAL Dollar recipients to put in the effort of helping the program

succeed by using it in trade, since they can merely exchange it for a federal

dollar and be on their way.

The program's existence is due in part to the Internet; Highberger and others

were working on a similar program several years ago which failed to materialise.

His contact information, however, was not removed from online local currency

directories, and when interested locals found his name on these websites, they

contacted him and REAL Dollars began.

Highberger said operating expenses should be funded by the interest received

on the money deposited, wisely commenting, "We're waiting to get things

stabilised before starting the loan program part of our currency."31

If the administrators can successfully resist all urges to touch the principal,

even temporarily, until enough confidence is established in the redeemability

of the money, then they may be able to begin performing a variety of services

with the money on deposit, currently estimated at greater than $50,000 to back

the REAL Dollars in circulation. The success of REAL Dollars, like that of many

other currencies, is still indeterminate. According to Sieverson, it takes five

years for a program to establish itself and gain enough momentum to be relatively

self-sustaining. Until that point, there are a number of issues which must be

considered carefully by local currencies, some of which are discussed in the

next chapter.

| Contents | Previous Chapter | Next Chapter |

Endnotes:

1 Links to other Local Currencies, n.d., available [Online]: <http://www.olywa.net/vision/links.html> [24 September 2000]; E.F. Schumacher Society, n.d. Available [Online]: <http://www.schumachersociety.org/cur_grps.html> [17 September 2000]; Ithaca HOURs: Other HOUR Cities, 15 August 2000. Available [Online]: <http://www.lightlink.com/hours/ithacahours/otherhours.html> [17 September 2000].

2 The most detailed and up-to-date listing from the Ithaca HOURs website had Mendocino's SEED program listed as still in the planning process as late as April 2001, the time of this writing, though SEED began operations in February 1999.

3 Donald Hof, interview by author, 26 September 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

4 Gary Pace, interview by author, 15 July 2000, Boonville, Calif. (Tape recording).

5 Dale Glaser, interview by author, 15 July 2000, Boonville, Calif. (Tape recording).

6 King Collins, interview by author, 13 July 2000, Ukiah, Calif. (Transcript).

7 Larry Sheehy, Who Are the People Behind Ukiah HOURs, 22 August 1999. Available [Online]: <http://www.greenmac.com/hours/who.html> [28 August 2000].

8 Barbara Conn, interview by author, 5 December 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

9 John Gibson, interview by author, 23 October 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

10 Steve Gorelick, interview by author, 5 December 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

11 Sita Francia, interview by author, 16 July 2000, Boonville, Calif. (Tape recording).

12 Lisa Sorg, "Time Has Come Today: The BloomingHOURS Project," Bloomington (Ind.) Independent, 16 September 1999, 6.

13 Devin Scherubel, interview by author, 16 October 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

14 Kathy Witkowsky, interview by author, 17 October 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

15 Gail Sullivan, interview by author, 2 October 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

16 Boog Highberger, interview by author, 16 October 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

17 Jennifer Kreger, interview by author, 17 July 2000, Mendocino, Calif. (Transcript).

18 Timothy Mitchell, interview by author, 16 November 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

19 Tony Samara, 24 November 2000, Re: Local Currency Survey

[Email to Andrew Lowd].

20 A copy of that survey can be found in Appendix

Three [pdf].

21 Linda B. Bourque and Eve P. Fielder, How to Conduct Self-Administered and Mail Surveys (London: Sage Publications, 1995), 12.

22 These were Value per Unit, Units Circulating, Units per New Member, and Units per Renewal.

23 Larry Sheehy, interview by author, 13 July 2000, Ukiah, Calif. (Tape recording).

24 Sarah Sieverson, interview by author, 26 October 2000 [phone]. (Transcript).

25 Susan Hofberg. Interview by author, 15 July 2000, Boonville, Calif. Tape recording.

26 Paul Glover, "A History of Ithaca HOURs," Ithaca HOURs, January 2000. Available [Online]: <http://www.lightlink.com/hours/ithacahours/archive/0001.html> [21 September 2000].

27 SonomaTime -- Sonoma County Community Cash, n.d. Available [Online]: <http://www.sonomatime.org/grow.htm> [19 April 2001].

28 For this example, it is postulated that no positive externalities are introduced by paying an unexpectedly-high wage; rather, the price mechanism becomes distorted.

29 Friedrich A. Hayek, Denationalisation of Money: An Analysis of the Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1976), 66, 75.